Black Panther (2018)

The Revolution Will Be Televised

“The poverty program was not designed to eliminate poverty”― H. Rap Brown

“I’m not Walt Disney. I do a lot of things Walt Disney wouldn’t do. Walt Disney doesn’t smoke. I smoke. Walt Disney doesn’t drink. I drink”― Walt Disney, PBS American Experience: Walt Disney

“We never see clearly what we over-identify with”― Craig Chalquist, Essay: Why I Seldom Teach the Hero’s Journey Anymore

Walt Disney studio’s Black Panther is, presently, the most popular film on the planet grossing over a billion dollars in sales in just over a month. It is not uncommon for features based on Superheroes to dominate the box office, but this is different. It is novel to see a big budget feature composed almost exclusively of people of color. It is also a welcome surprise to see so many women in dominate roles as warriors and scientists. But the appeal is not due to tackling black empowerment or the first rate craftsmanship.The film’s resonance lies in the superhero taken part in an overt political upheaval. This theme dovetails with a global uprising against established elites. It is important to remind ourselves that Walt Disney company is interested in revenues, not politics. This “revolution” must sell tickets. In that respect it is a triumph of harnessing the socio-economic zeitgeist, rather than advocating dangerous ideas. Think of it in terms of product. Coke is the “real thing”, but a soft drink can never get “too real”. Ditto for our African Prince. He is the suggestion of revolution, rather than a revolutionary.

The structure of the film relies on familiar plot devices. We have a world threatened by those coveting a valuable resource, vibranium located in the kingdom of Wakanda. Think of the unobtanium in Avatar. Our superhero possesses technological prowess, think of the James Bond or Mission Impossible franchises. There is a family feud of biblical proportions, think Luke Skywalker and his father. The challenge in these films is to seamlessly integrate the eternal quests with the pyrotechnical displays. The battle or chase must not feel disjointed from the exposition. The first half hour does a commendable job of giving the history and background. Wakanda is a land that, although economically rich, safeguards itself behind the facade of being a “backward” third world nation. The story relies an internecine struggles within the extended family, think of the Hebrew bible rivalry between Isaac and Ishmael. Unfortunately the original sin, a fratricide involving two princes, is muddled. It becomes unclear why the Prince’s son is left abandoned in an American ghetto. Since this is a revenge narrative it is problematic for the motivation to be opaque. Why does Wakanda station spies in foreign cities? Was it really necessary for one Prince to murder the other? This flaw is obscured by fast moving action sequences in which the various wronged parties are assigned their “good” and “bad” roles. Ironically the violence would have been enhanced with a better understanding of the setting and grievances.

The storyline is dynamic. The Wakanda world has it’s own internal struggles. The writers took the sylvan paradise city of Shangri-La from Lost Horizon, and infused it with gadgetry from the futuristic cartoon The Jetsons. This split has a political tinge as there is an internal kingdom of luddites who eschew all modernity in favor of the old ways. Despite the interesting narrative the screenwriters stumble in shaping the characters. There is an inordinate amount of time wasted creating Ulysses Klaue, a classic superhero villain who traffics in underworld crime. He is quickly dispatched in a sequence where he organizes the theft of an artifact, an ax made of vibranium, being held in the British museum. This weapon, whose existence leads to a complicated interaction with a CIA agent, also vanishes from the plot. These blemishes pale in comparison to the quiet, non-action, dialogue. These sequences are merely book-marks segregating swords clashing, rhinos charging and space ships blowing up the scenery. The banter between family members, prominent officials and intimate companions is wooden. One feels as if the characters should have turned to the camera and stated the scene’s intention: “I am the funny younger sister and I have a jokey relationship with my brother” or “I am the former love-interest who is in still interested” or “I am the general who will follow the rule of law over emotional considerations”. The comic book origin of the project unfortunately seeps through in these embarrassing interludes.

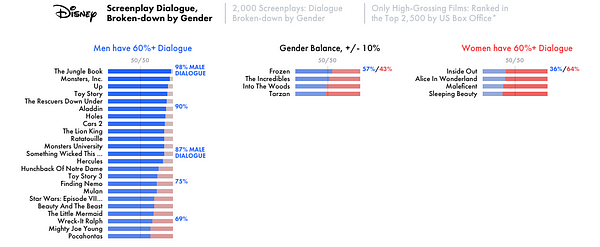

The writer/director, Ryan Coogler, had a great deal on his plate balancing so many intricate facets. Sadly the spoken word took a back seat to special effects, scenic and costume departments. Kudos to the integration of African motifs, designs and music. They were delightful and avoided the trap of being overtly patronizing. Given the history of Western exploitation of Africa, Coogler must have been weighing the ramifications of appearing insensitive in every single frame. The contemporary movie industry relies on world distribution for their product so a misstep would have clear economics ramifications. Thus far, foreign receipts for Black Panther make up half of the total revenue. This wasn’t the case in the early 1950s when Walt Disney produced, Song of the South, a paean to antebellum Dixie featuring a live action plantation hand, Uncle Remus, as the narrator. Not only was the studio indifferent to foreign revenues, they had no qualms about alienating people of color. Times have changed. Song of the South has been out of circulation for decades in any format. Disney’s new found social conscious has recently produced Zootopia, an animated feature that preaches against the evils of stereotyping and racism. There have also been other recent forays tapping other cultures: Moana (2016) has a Polynesian motif and Coco (Coco) revolves around the Mexican day of the dead tradition. Disney hired an army of experts to supply enough ethnographic detail to mask the uncomfortable history. Black Panther brings this Disney oeuvre to Africa, which is a peculiar setting for a comic book money machine. There is also the conundrum of avoiding the idea that this film is overtly anti-European.

The two central Caucasian characters share the bifurcation of the two rival Princes, T’Challa and his cousin Killmonger. One is a sanctioned paradigm of virtue whereas the other is outside the law. The colorful arms dealer/assassin/terrorist, Ulysses is, unfortunately, eliminated after two brief appearances. Everett K. Ross, a CIA agent ally, joins T’Challa and fights the good fight by using his pre-spy skills as an air force fighter pilot. This is where Black Panther’s forays into history become questionable. Is it appropriate for the “good guy” to be a member of the American spy agency that, among other things, betrayed Nelson Mandela to South Africa’s Apartheid government? Once again Black Panther is light entertainment, not history. But the choice signals a larger theme of sanitizing real events to give an upbeat gloss. Yes the CIA is involved, but unlike the bad ole days, they are a benevolent force supporting a just cause.

This breezy appropriation of real life is also illustrated with Nakia, T’Challa’s love interest. She pursues social justice instead of resting on her laurels as a powerful figure in the Wakandaian court. She works with enslaved women who are caught up in a “Boko Haram” hostage situation outside the kingdom. The Prince personally brings her back to witness his coronation. Interestingly the film eschews the standard ploy of having the estranged couple unite after their adventure at the end of the story. The Prince evolves to adopting her worldview of tending to the needy. Interestingly the denouement centers on America, not Africa. T’Challa appoints her to run a social center in Oakland where the “evil” cousin was raised. This reaching out to outsiders is a direct rebuke to his father, the former king, who was a hard line isolationist. The kingdom will now engage with non-tribal people within a safe context. The United States, the richest country in the world, is chosen as the area most in need of foreign aid. It is another strange twist in a film that is riddled with odd contradictions. What about helping Africans? The truth is trying to shoe-horn the new treatment of neighboring countries would raise too many unsettling issues. Does Wakanda accept refugees? Does economic support include technological transfers information? Cash payments? What sorts of governments would they support? These questions seem ludicrous, except when you consider that the filmmakers chose to set the story in this particular geographic location and make overt references to contemporary political trends.

The Black Panther himself faces a unique black superhero burden of having to define “evil”. Batman, Superman, Spiderman and the pantheon of superheroes are at war against generic badness. There is no righteousness in the backstory of the Joker or Lex Luthor. But what about Killmonger? This is a chosen son who was abandoned to the harshest of city streets. Prior to his life of crime he lived a Hortio Alger story and became a decorated military hero. Most importantly the motivation for teaming with Ulysses was not riches or self aggrandizement. It was a part of a master-plot to re-take Wakanda in the name of his dead father, who was murdered by his uncle, T’Challa’s father. Rather than a venal sociopath, he might be seen as a hardscrabble Robin Hood . If Black Panther spawns a prequel, it would be interesting to cover this avenging angel’s backstory in the gang-ridden streets of Oakland. The kingdom of Wakanda would be an arrogant refuge in need of a revolution, rather than a noble paradise. But this might prove too much upheaval for a lucrative franchise. This sort of entertainment relies on black and white, not grey.

It might seem too much of a burden to delve behind what makes the Panther run. Perhaps it is enough to simply enjoy the action and focus on the positive evolution of expanding opportunities for non-traditional points of view. It is progress when a company created by an infamous misogynistic bigot creates inclusive family entertainment. It is fun to see the creator of the character, the nonagenarian Stan Lee, appear in a cameo at the gambling table. Let’s put away the carping and on board the bandwagon. Rolling Stone magazine’s review is typical of the hyperbole: the film is “A landmark adventure”, “a new film classic” and “an answered prayer. We have a narrative that shows a diverse group, resisting the urge to draw back into the lull of their wealthy enclave. Popular leaders have made horrible choices. There is scandal followed by turmoil, but the righteous prevail in a comfortable, safe outcome. Why nitpick over minutia? After all this isn’t a blueprint for future government policy but merely entertainment. This is a “feel good” progressive comic book, turned mainstream Hollywood film.

Strangely the urge to embrace the important breakthroughs in casting and storytelling might blind the general audience to the continuation of the same problems under a slicker veneer. This film brings to mind George Harrison’s efforts to help the flood stricken country of Bangladesh in 1971. He organized a relief concert with many celebrities. This practice has become de rigueur inspiring a tradition in the industry (Live Aid, Farm Aid…) Despite Harrison’s wonderful legacy, and good intentions, his anthem from that gathering, the song “Bangladesh”, is forgotten and considered condescending and inappropriate. Could Black Panther suffer the same fate?

Africa continues to reel from centuries of unspeakable crimes perpetrated by the same societies that created this film. One does not need detailed knowledge of King Leopold’s mining exploits or the horrors of the middle passage to sense an unease about using this continent as a background for American bromides about goodness. Given the economic and ecological devastation one might draw a parallel between this American production and Leni Riefenstahl’s Tiefland. This sylvan fantasy, based on a Spanish Opera, was shot by the infamous director during the carnage of World War II. It apparently has beautiful scenes capturing European peasant life. Critics have even gone so far as to say this Nazi backed production is, thematically, anti-fascist. Nothing however can hide the fact that many of the extras were taken from forced labor camps and some have been rumored to have perished at Auschwitz. It might seem an outrageous comparison. It would be interesting to know, however, if refugees drowning the the Mediterranean and victims from conflicts from South Sudan to Nigeria to Kenya might see Black Pantheras the same sort of exercise in dangerous, frivolous, escapism.

Unfortunately America has a way of entertaining itself into a haze of cruel indifference. The present impact of reality TV can be seen at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Whatever one’s political stripe it is fair to say that political discourse, always a blend of fact and fantasy, has grown exponentially towards the latter. Having dreams can inform. But relying on fantasies, can lead to nightmares. Could this stylized fairytale based on a comic book propagate simplistic notions about economics or foreign policy? Is it unseemly to appropriate ethnographic stylization and sanitize history in the service of expanding entertainment markets? It seems absurd, but one might say the same about the current state of world affairs. In this light Black Panther needs to be scrutinized. Let us take the good and the bad.

It is wonderful that so many performers and stories, that heretofore were silenced or banished, have come to the fore. This film, despite minor considerations, does an excellent job of translating the thrill of a comic book saga to the large screen. One wonders if future generations might see the gloss of a Pax Americana as equally offensive as Song of the South. Perhaps Disney’s pursuit of overseas revenues, via careful local adaptations, will be viewed as a new form of colonialism. Could economic disparity cast a pall over the well meaning nods to cultural stylization? Could the increasing divide between the “haves” and “have nots” undercut corporate marketing to disenfranchised communities? Perhaps cocky insolence fuels the the ubiquitous allure of American films, celebrities and sports teams. One wonders, however, if the fandom has a shelf-life. Will the United States face its own angry, lost cousins? Let’s hope they are not mistaken for Disney imitations.