Phantom Thread (2018)

Folie À Trois

Already, he was dreaming of a refined solitude, a comfortable desert, a motionless ark in which to seek refuge from the unending deluge of human stupidity. Huysmans’ Jean des Esseintes, the protagonist of “À Rebours”

Dial me a Valentine, She’s a smooth operator,It’s all so calculated, She’s got a calculator, She’s my soft touch typewriter and I’m the great dictator; Two little Hitlers will fight it out until, One little Hitler does the other one’s will………. Elvis Costello, Two Little Hitlers

A renowned tailor is ill and collapses on a wedding gown recently completed for the Princess of Belgium. His staff of seamstresses must work all night to repair the damage done to the dress. This might be called the “action sequence” in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. The film is about a love affair between an English couture designer and his muse, a stunning tabla rasa. This might not seem the grist for high drama but in the hands of master craftsmen (and women) anything is possible. Anderson, and his ensemble of top talent, manages to make a profound statement with a minimal plot peopled with dreary characters. The press has rightly paid tribute to the leading man, Daniel Day Lewis, but it is the sorority of Vicky Krieps and Lesley Manville that makes the production sing. This fragment of a romance between an obnoxious egoist and a myopic striver rises to be a meditation on love, work, passion and artistry.

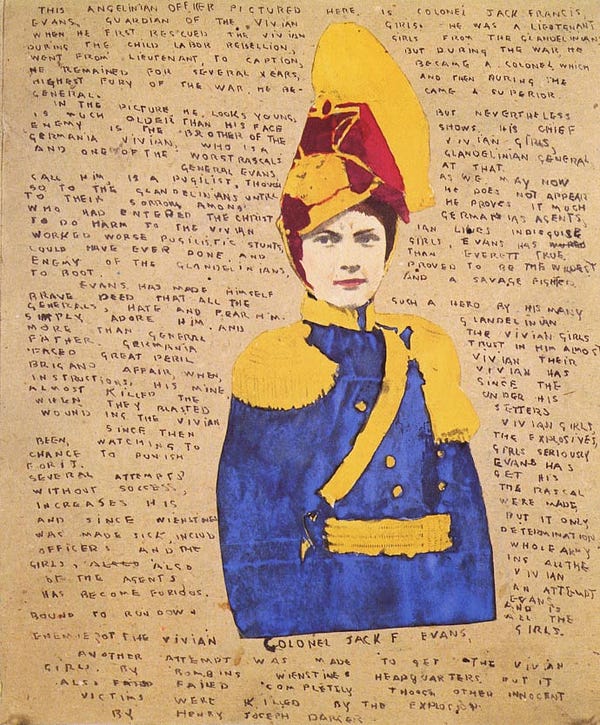

Many extraordinary people find basic social interaction to be abhorrent. Then there are those who must create their own world to interface with the outside. A third party, an army of factotums or a beleagured relative, must be always on hand to translate their needs to a bemused public. The protagonist in Phantom Thread is part of this unhappy tribe. The lucky ones retreat and become hermits accepting a solitary existence. Their work is discovered after their death. An example would be the collage-artist Henry Darger, who spent his childhood in abusive institutions. He lead a radical as a hermit working menial jobs until dying of old age in obsurity. His multi volume notebooks illustrated his imaginary world of armies of litte girls battling civil war soldiers. He had a difficult life, but it might be crueler to be someone such as the artist formally known as Prince. He died of a drug overdose in an elevator in his self-designed music fortress. His body was discovered after many hours by his dedicated staff. They knew he was in trouble, but his idiosyncratic rules prevented anyone from saving him. Reynolds Woodcock, the protagonist in Anderson’s feature, is the spiritual brother of this musical dynamo.

The opening sequence gives us the two main characters and their unhappy household in post war London. Reynolds is a master couture dressmaker. His sister, Cyril, is the business manager. There is also a third wheel, a girlfriend. One senses she is the latest in dynasty of unhappy models who serve brief tenures as companion and muse. The sister does the dirty work of delivering the news, that her services are no longer desired, while the brother retreats to a refuge in the country. These establish their roles. This is a “foilie a deux”. The sister is his manager whose sole purpose in life is to indulge the work-horse brother and watch the bottom line. She loves him, in her way, but business is paramount. He has license to be myopic and rude. Into this dystopian marriage comes a replacement muse for their fashion empire, the “House of Woodcock.” Alma, brilliantly played by Vicky Krieps, is the coquettish waitress in the country inn. He orders everything on the menu. He is famished and he asks her to dinner. He will devour her and everything she serves him. This breakfast encounter is a sample of the tour-de-force technical execution of the story by director and his team. Reynolds’ fawning combined with Alma’s blushing has the facade of a Norman Rockwell tableaux coupled with the gravitas of a Vermeer still life. The minimalist story glides on in the hands of consummate professionals who give the perfect tint to the clothes, the correct amount of shade to the setting and the right amount of background noise or music.

This film plot, rather than being the centerpiece, is simply the thread that weaves a tapestry of intense moments. This is a work of glances, rather than dialogue. Anderson’s writing and direction have been acclaimed but it turns out the auteur also worked as his own cinematographer. Is this film somehow autobiographical? Obviously this director knew EXACTLY what he wanted and put together a team of masters: from the gaffer (Michael Bauman) to the camera operator (Colin Anderson) to the costume designer (Mark Bridges) and myriad department heads. One need not be an expert in mid-twentieth century English fashion shows to know that this is a picture perfect rendering of such an event. The position of the chairs, the age and dress of all the participants, the choreography of the models, all speak to hours of combing over old photos and a days spent in libraries reading source material. All the homework renders an delightful visual feast of convincing detail.

The tenderness between Alma and Reynolds morphs into the gothic as Reynolds reveals himself, his art and his demons. The exposition reveals a childhood of loss coupled by a harsh apprenticeship as a dress-maker. This is all at the hands of his doting widower mother. He copes by fastidiously mastering his craft. He tells of rituals involving sewing mementos into the lining of garments, such as a picture of his mother in the jacket he is wearing. The woman was certainly attentive and deserves praise, but clandestinely wearing mom on his chest? One senses Norman Bates might have done the same thing if he had the talent. The overt darkness falls when the innocent is led to the dressing table as Reynolds mood shifts from suitor to cattle handler. One suddenly realizes what hunters mean by “dressing” an animal. This is an initiation rather than a date. Alma is stripped to her underwear and measured. Anderson choose to convince rather than shock so there is no nudity or sex in the entire film. Alma is both offended and intrigued. Is this how rich people behave?

Alma stands at the butcher-block alter of the fitting room. The honor of being chosen by a world renowned designer overrides a mammalian desire to seek refuge. Despite her best efforts the fear shows through the muslin. The terror increases with the arrival of the assistant tormentor. Cyril fails to introduce herself. Why waste time when this encounter is probably a one night alteration. There is no escape for the callow waitress as his beloved sister literally sniffs her out. Cyril inhales and comments on Alma’s perfume. Alma is so taken aback she thinks she might be smelling something else and comments, “we had fish for dinner”. The artist begins his artistry and shoves a notebook in his sisters hand. She dutifully scribbles Alma’s measurements. The harshness of the brother’s treatment of Alma and Cyril, coupled with the sister’s indifference makes for an excruciating few minutes. Reynolds pressing the tape measure intercut with close-ups of the sister writing the numbers hammers the home the dehumanization ritual. She passes the test and becomes a subordinate member of their cliche.

Alma’s ascension from the obscurity of the provinces, to the height of the London fashion scene. One would expect her to covet her new-found wealth more than her mentor. His charm might fade in direct proportion to her intimate knowledge of the man himself. His dressmaking virtuosity equals his contempt for anyone, or anything, that fails to match his mood or prevents him from working. These traits are coupled with a deranged obsession with his dead mother and devotion to his misanthropic sister. Given Reynolds’ disposition, it would be natural to assume that Alma’s interest might be in the castle rather than the king. In fact the film hints at her coming betrayal. There is a constant cut away to her divulging an inside view of the House of Woodcock to an attractive young doctor. This physician is also treated with contempt by her sick husband. Alma’s supposed infidelity narrative culminates in her DEMANDING to go dancing on New Year’s Eve shortly after their marriage. Unbeknownst to Reynolds she has been invited to a party by the handsome doctor. She abandon’s her obstinate husband who prefers to bring in the New Year drawing dresses. She is soon on the dance floor in one of his magisterial garments, amidst a magnificent pageant. The celebratory spectacle is itself couture artistry (Kudos to set designer Veronique Melery). Reynolds frets and paces in the manner of a jilted sophomore and finally goes to the party. He watches her jealously as the huge paper mache incarnations swirl. There is suddenly a disturbance. One of the live puppets stumbles nearly hitting Alma. There is the suggestion of some drunken violence. He rushes to her rescue. She has escaped, unaided, to safety. There was never any doctor in the house. Reynolds arrives expecting to be hailed as a white knight; or at least given proper deference for his concern. She is having NONE OF IT. She glares. But ironically it is the wrath of love. The whole scene is constructed with the expectation of a revelation of an affair or a relationship-ending showdown. The result is a strange affirmation of their bond through the strife of discontent and disapproval. She knowns his love is exclusive to his mother. His trade is a fool’s errand to secure the admiration of this, long dead, woman. She knows she must begin the laborious process of winning him back. This is her painful, humiliating path to love. One can understand her ambivalence at his supposed gallantry. It is merely the suggestion of affection, which she knowns is absent. After all, she is not a dress.

Undermining expectations is the phantom thread that permeates the film. The audience is led to thinking that this aesthete sophisticated couple will use the provincial waitress as a temporary muse. Instead the mysterious hay-seed co-opts the city slickers. A conventional film would paint her as a social climber interested in the glitz and power. Eve in the seminal All About Eve is the paradigm of the ambitious ingenue who betters the sophisticates. Alma is a striver, but her desire is as unworldly as Reynolds’ passion for dresses. She genuinely falls for the master tailor. She loves him. The normal cycle of having the muse be discarded is undone by the fact that she is as alien as her husband and his sister; in fact more so. At least they possess a backstory. We have only the fact of her German accent and lowly station in life to build an understanding of her. Alma is never asked about her history and there is no exposition revealing her roots. How did she end up in a English village? What is her nationality? Is she a refugee? She, on the other hand, studies her charges to the same degree they physically measure her. She understands their deficiencies while they are oblivious to her aspirations. She is treated as someone who should be seen, but never heard. The brother and sister mistake her for a child. She is really the parent.

There is a telling moment when a Belgian princess arrives to be fitted for her wedding dress. Reynolds has crafted the garments for all the benchmark moments in her life: baptism, confirmation, coming out… Alma is dutifully playing her part as dresser amongst the sea of bridesmaids and Reynolds’ asistants, who have matching uniforms. She walks up to the princess, who is being fitted. Although Alma is dressed as a senior member of staff she introduces herself to the royal and adds, “I live here”. It is a watershed moment in a film that is replete with brief conversations, glances and non-verbal exchanges. It is so quiet that a casual observer might mistake it for merely an odd aside. Certainly Reynolds and Cyril think of her as merely a dedicated cog in their machine. Alma certainly has had a special status up to this point, but is as if she were a family pet hovering in the background. Alma’s mission to be a Woodcock takes on an air of a religious pilgrimage. Normal people might be interested in marrying into the family. She wants the family. Her “love” is a Romantic sublime rather than the careful sentiment of a bourgeois spouse . Although the plot is Dickensian, the ardor is pure Emily Bronte. She is Heathcliff in his desire for Catherine. This isn’t about the here and now, but rather eternity. Alma’s small passing phrase — “I live here” — might be more accurately translated as “I am the house and the people in it”.

When Reynolds finally proposes, her immediately answer is… silence. He is forced to ask again. She seems hesitant in her acceptance. Her pause is rooted in knowing she has formed an unbreakable bond by assuming the role of his new mother. This was achieved through nearly killing him. As an adult with conventional standards of morality Alma’s putting her mentor/husband at death’s door is abhorrent. In the context of a eternal religious act she is merely playing her rightful role. She is the guilty innocent while he is the culprit victim. The artist is held captive by a righteous mother defending her child. The twist, however, is that she is the one causing him to be sick. Munchausen syndrome by proxy, a disease where caretakers purposely make their charges ill in order to come to the rescue, is not a conventional path to love. Unfortunately Reynolds is so damaged, there is no other choice but to make him physically in need of a pampering mother. It is pure madness, but how else could she establish herself as the new matriarch?

Alma’s fierce parenting goes beyond cuddling. She knows how to protect her charge on the playground. This fierceness is shown when Cyril forces Alma and Reynolds to attend a pre-wedding party for a rich patron. The client, in one of Reynolds’ creations, collapses in an alcoholic stupor on to the banquet table. Alma feeds Reynolds’ outrage that this woman should dare disgrace the house of Woodcock by wearing her vulnerability for all to see — while wrapped in one of his signature creations! You may wear one or the other, but not both. Whereas the enfant terrible, never used to doing the heavy lifting, might have stewed in anger, Alma organizes the cavalry. They burst into the client’s bedroom and Alma tears the dress off the comatose woman, much to the chagrin of the lady-in-waiting. The scene has the air of a stern mother taking back her son’s favorite toy from a playground bully. It ends with an exuberant Reynolds carrying his love, the garment, down a London street. Alma is also by his side. His joy extends into the following morning’s meal, a time when our boy is usually notoriously cranky.

The breakfast scenes, of which there are several, are the showcase for the brother-sister alliance. In addition they become the stage for Alma’s steady climb up the ladder. The sister plays her pampering role and tries to reprimand Alma for being too forward. Alma completely ignores the warnings, in fact she doubles down with opinions that define her as a distinct person, rather than merely a toady. Anderson, purposefully, never lets their rivalry come to a boil, as the this is a film about simmering. The two actually respect and admire each other. Cyril senses this new muse is different and can possibly be relied on to assume the burden of managing the brat. There is a confrontation over sending for medical help for an ailing Reynolds that show another of Alma’s clever calculations. Reynolds, despite his illness, refuses a doctor. The doctor retreats after Reynolds curses him out. The medicsheepishly leaves while addressing BOTH women as Miss Woodcock. They reply, IN UNISON. The doctor exits. One expects a kerfuffle and instead there is… silence. A silence that speaks to Alma’s new role as the brother’s protector. Cyril accepts the facts on the ground as Alma bolts the door to her brother’s room. This resignation is probably coupled with relief. The truth is Cyril find the suffering Reynolds… insufferable.

Reynolds’ childishness comes to the fore when a client rejects him. Cyril must endure his tantrum which is coupled with an admonishment to her for not revealing that this customer is going to a rival. Cyril responds to her brother’s whining with a curt, unsympathetic dismissal. Reynolds becomes unhinged and in a line reminiscent of the TV comedy “Arrested Development”, cries out “I’ve made a terrible mistake”. He is referring to his marriage. In the middle of the tirade Alma, stealthily, walks into the office. Cyril fails to mention the entrance and the new bride hears every word. Reynolds suddenly realizes his wife is within ear-shot but simple goes on with his attack. In the end Alma and Cyril CALMLY ignore him and go about their business. Reynolds, in a childlike whimper, carps at their unnerving politeness. His horrendous behavior is their fault. In short, the adults carry on and let the baby have a good cry. In effect Alma has superseded Cyril as the primary caregiver. The old nanny appreciates someone else carrying the burden.

Phantom Thread is a gorgeous dark fairy tale that culminates with, yet another, upending of expectations.There are stylish monsters that move in a world of princesses and aristocrats. There are magic potions, of a sort, and a wonderful fairytale ending that is imbued with melancholy. Alma has demonstrated she is clearly as deranged as her mad tailor and his sister/manager. The closing reveal of Alma’s dreams makes us wonder whether her prince might have been better off remaining as a frog. The modern day version of The Frog Prince story has the Princess kiss the amphibian in order to trigger the metamorphosis into a handsome man. Anderson seems to channeling the original version where the frog is smashed against a wall. The cudgel that bashes the House of Woodcock is hewned of a bourgeois provincial fantasy. Alma dreams of pushing a perambulator accompanied by Reynolds. As the audience we know that the the happy family tableaux is sew together by the excesses of three extremely damaged people. A house covertly divided against itself, cannot stand. The logical extension of this twisted love story is that Alma might not be able to reverse the occasional attempted manslaughter. Going “too far” might provoke suicide, or murder suicide, or double suicide. The exterior, however, is exquisite. But the Woodcock castle sits in a pristine setting. Why linger on the horror when you can take in the scenery.

The 1950s London portrayed in this film is replete with beautiful cars, houses, people circulating in a well ordered, hand-crafted world of bespoke objects. There is no hint that a decade before bombs were raining down, possibly from Alma’s native land. Unpleasantness might still be at hand but it a world away from the drawing rooms of one of the aristocracies’ favorite dressmaker. We are in a beautiful place with extraordinary people dedicated to making the most beautiful garments in the world. This sort of passion can produce art that takes us all to the sublime ecstasy. One need not know the artists struggle to relish the work. But we need to recognize that this sort of unworldly dedication comes at a steep price. Anderson puts a beautiful veneer on a story about isolation, drudgery and unhappiness. Krieps, Day-Lewis and Manville deserve a long standing ovation for making these desperate people so dignified in their absurd struggles. Cyril’s determined stare is a paean to the plight of those who serve artists. Alma captures the terrifying, yet beautiful, glow of the true believer. She is the Joan of Arc of high couture. Reynolds is the prophet with the power to make silk from a sow’s ear. And yet we are talking about… dresses. Ah yes, but what dresses!

Is it worth the struggle? Most compassionate people would applaud Cyril leaving the incestuous cult to pursue a career that allowed self-actualization. Alma would be better off with a true partner, than a madman who needs a episodic brush with death to remain faithful. Reynolds would do well to put down his sewing needle, forget about his mother and smell the roses before his partner is indicted by the authorities. Unfortunately normalcy is never an option for those touched with an unearthly gift that, in turn, is a curse.

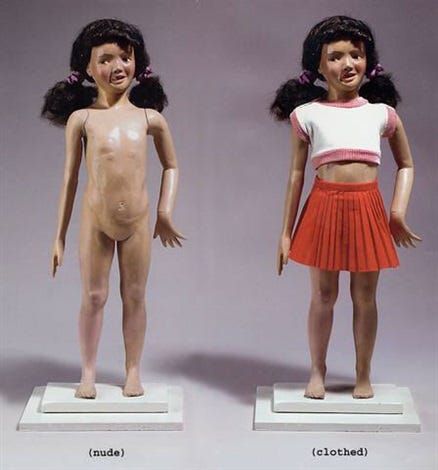

The real life Morton Bartlett would have been a contemporary of the fictional Reynolds. This mid century, American graphic designer spent all of his free time creating exquisite, lifelike plaster dolls of children. He painted them and hand made all their clothes. This fastidious work culminated in him staging the dolls in dioramas representing domesticity. For nearly three decades this was his labor of love. He suddenly stopped after a magazine ran a story on his hobby entitled “The Sweethearts of Mr. Bartlett”. He carefully wrapped up his creations in newspapers and placed them in custom made wooden boxes. He died as he had lived, alone in his obscurity. His work was rediscovered after his death.

Anderson’s fairytale imagines Morton being dragged into the limelight, forcing an intimacy outside of his art. The movie asks whether dolls, or dresses, or photographs, or films… are worth a life. This question might not have resonance with an average person, but it means the world, literally, to those whose being is their craft. There is no other path. That is the triumph and tragedy of this grim fairy tale. Enjoy the beauty and know that peoples’ essence goes into making extraordinary things. We wish for their sanity and might feel guilty in enjoying the fruits of their pathology. But we owe them applause in recognizing the other worldly accomplishments. In the end this fleeting nod of recognition gives them a glimmer of satisfaction before work is begun on another dress or doll or painting or photograph or movie.

It has been said Mr. Lewis is leaving acting and that this is his last film. I’m sure Anderson, Krieps and Manville have battled similar urges. This is the plight of all who reach for perfection. We hope that Mr. Lewis is happy in his retirement…. But as an audience, we might have Cyril’s dark desire to keep the act moving. We share more with these people than we want to admit. We all appreciate a well made dress… and a well made film. No nudity, no pyrotechnics, no violence, little cursing, no gore, a trace of a plot, no sex, minimal dialogue, no special effects, monomaniacal characters and yet… it was riveting. A master at work.